I am a South African researcher, registered as a doctoral student at a UK-based university, and am studying autism and play. In my work, I have considered how to ethically conduct research in Global South settings, where there is limited research on either of these topics. This blog shares elements of my approach which might be of use to those seeking to undertake similar research projects.

Most things we know about autism and play come from countries in the Global North, but why is this problematic? It matters because nearly 80% of people live in the Global South, but only a tiny fraction of research about autism and play captures what happens in these contexts. This means that in a country such as South Africa, autistic children are taught in schools that cannot access culturally relevant research to inform their policies and practices.

As autism research in Sub-Saharan Africa is slowly increasing, it is crucial that researchers do not merely parachute ideas from the North. It is important to ask questions such as: how can we make sure that we represent research participants respectfully? How do we honestly represent local knowledge without comparing to existing, largely Northern, understandings? Or, in my case: what does teaching through play look like in South African autism schools?

I have identified three important steps for conducting research ethically in this context:

1. Engage in bottom-up, exploratory, and participatory research approaches

When researching in a context where little is published about autism and play, it is important to explore a research question from a bottom-up approach. This helps avoid parachuting ideas that are not applicable in the given context. In my case, this meant spending six months in three South African autism schools to explore what playful teaching could look like in these contexts. I included a one-month familiarisation period in each school before starting data collection. During this time, the information and consent forms were discussed in detail and participants had plenty of time to ask questions. Following a playful participatory research design, I worked closely with the people who engage with the education of autistic learners daily: teachers and teaching assistants. As active participants in the research process, they shaped the knowledge production of what play meant in South African autism schools. Together, we explored spaces where playful teaching took place, what playful practices looked like, and what contextual challenges there were to play in schools.

2. Engage in genuine collaborative partnerships with South African organisations from the very beginning of research

To ensure that research is contextually relevant, the importance of engaging in genuine collaborative partnerships cannot be emphasised enough.

Local academics should be active participants in shaping the research. From the inception of my PhD project, I proactively grew my South African networks to include other researchers working with autistic learners and, more widely, in inclusive education. I attended various South African conferences to learn from and connect with local academics. Importantly, my network did not only grow in terms of researchers, but also practitioners, caregivers, and community members. These critical networks, which were formally recognised as my South African PhD advisory board, played an important role in designing the research. For example:

- Suggesting the inclusion of teaching assistants in my sample (not just teachers)

- Identifying and sampling autism schools

- Piloting the research and subsequently changing the research focus from ‘playful learning’ to ‘playful teaching’

- Critically engaging with the research instruments

- Pointing me to relevant South African literature that I could not access from the UK

All of this gave more depth to my research and made it more responsive to the unique realities of this context. Creating genuine partnerships, this work demonstrates, requires going beyond viewing South African researchers as ‘administrators’ of ethics. The rigour of all research conducted in South Africa must be ethically and scientifically reviewed by a South-African based ethics committee. I liaised with the University of Cape Town and was guided by a South African supervisor as I progressed through this committee’s process.

3. Respect local data ownership and rules of ethics

It is vital to respect local data ownership. In my research, in the first instance, the data belongs to South Africa. To ensure co-ownership of the data between the UK and South Africa, an official legal transfer agreement had to be set up between the University of Cambridge and the University of Cape Town. This also had to be reflected clearly in all consent forms.

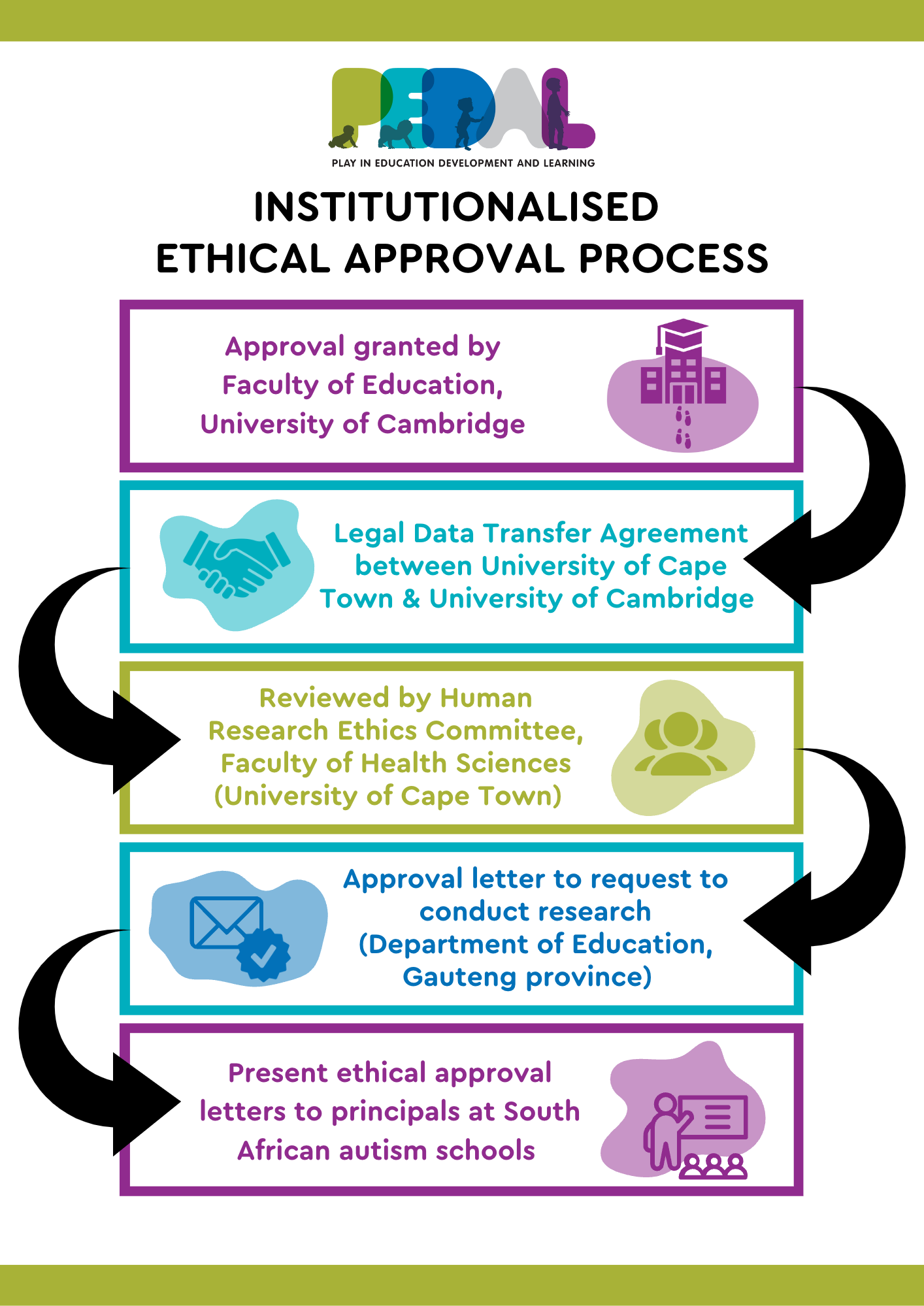

Please see below an infographic which outlines all of the formal steps that need to be taken before starting this research process.

The above process highlights that conducting ethical research in the Global South, where little is known about a research topic, requires time and thoughtfulness. There are no shortcuts, and ideas should never be parachuted from a Global North context. Knowing which steps are important can make these processes more visible and encourage more researchers to expand their research interests beyond Global North countries in an ethical and respectful way. Through this, it is hoped that autism and play research can move forwards and be inclusive of all children.

Further Reading

To read more about going beyond Western codes of ethics when researching in the Global South, refer to the following:

- ‘Going deep’ and ‘giving back’: strategies for exceeding ethical expectations when researching amongst vulnerable youth (Swartz, 2011)

- Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012)

- Researching ethically across cultures: issues of knowledge, power and voice (Robinson-Pant & Singal, 2013)

Further Resources

You can also find out more from Stephanie and our colleagues in the Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER), the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, and the Faculty of Education Students’ Association (FERSA) here:

- Navigating ethical research around playful teaching in South African autism schools: stories from the field (Stephanie Nowack)

- Gaining Research Permissions in Rwanda and Tanzania: Engaging Locally and Building Integrity as an Outsider (Dr Emma Carter & Manuel Kernen, FERSA)

Stephanie Nowack

PEDAL PhD Student